Conflicts & Origins: Making Compelling Characters

One of the main appeals of tabletop roleplaying games is the practice of creating a specific character—their strengths, weaknesses, past, personality, and more—and then expressing and exploring that character through play. Seeing how your character changes the world, and changes in response to the world, throughout play can be the primary source of enjoyment for many people in the hobby, and that's why it's also one of the main focuses of Dungeon World 2.

But what makes a good character? How do you tell a compelling story with a group of them? What kinds of decisions are dramatically engaging? How do you make those decisions without feeling railroaded or forced in your portrayal? How do you butt heads with another PC in a way that drives the story forward instead of bringing it to a screeching halt?

"We have spent decades arguing about dice systems, experience points, worldbuilding, and railroading. We have spent hardly any time at all thinking about the most basic tenets of storytelling. The stuff that if you talk to the writer of a comic book, or the showrunner of a TV show, or the narrative designer of a video game, they will say is second nature to them." - Quinns Quest Review of Slugblaster (starts at 28:50).

Here is a short summary of what my answer is, for Dungeon World 2 and many other TTRPGs.

What Makes a Good DW2 Player Character?

These are things that, ideally, all PCs in a game do in ways unique to each of them. They also work really well in other games.

- They Do Awesome Things like riding a dragon, shooting lightning, or phasing through walls. This is the starting point of character creation for many, and early players get excited to do said awesome things in play. We mostly want to handle that through Class design and advancement, as detailed here.

- They Care about the world and its inhabitants, and actively engage with them rather than avoid them. No one stays an island or lone wolf for long. Even if they don't get along with everyone, they should get along with at least a few people.

- They Want Something, or several somethings, which drive them to take risks and make decisions that might not always be smart but definitely feel right for them.

- They Have Dramatic Flaws, such as vices, limitations, blind spots, or obsessions, that make their life more difficult in unique ways. The wrinkles of these flaws provide texture and depth to the character by creating challenges that are internal, rather than just external. It's even better when these flaws come into direct conflict with each other or something else the character wants—or believe they want.

- They Express Themselves in scenes through decisions, words, and actions. They don't need to talk necessarily, but might have detailed body language, obvious emotions, or specific habits or interests. How do you feel about what just happened? What does it look like when you act on it?

With those ideals in mind, we've been trying to build mechanics that encourage these aspects in player characters without forcing them; that are comfortable but not ignorable. This is what I've been grappling with for Dungeon World 2.

What We've Tried

In vBlue we had Drives, which included a few sentences about your past and some ideas on how the Drive might be resolved. It was fairly simple, but felt mostly ignorable other than at the beginning (when you tell others about it) and the end (when you resolve it).

In vRed we tried fleshing out each Drive, calling them Ambitions and adding mechanics to interrogate and twist your backstory over time. This hypothetically works as intended, but was too long, very rigidly structured, and developed far too slowly to feel rewarding.

We want to retain flexibility without sacrificing direction, so in the Final Alpha, we're trying two new things.

New Origins

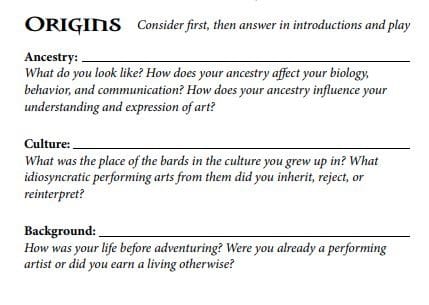

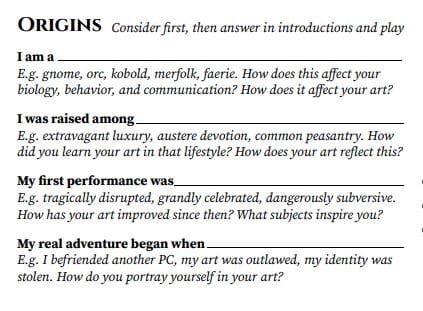

Where in Blue and Red we asked open-ended questions about your Ancestry, Culture, and Background, now there are Class-specific prompts about your past that can be filled in. While the answers can be anything, the examples below provide plenty of ideas, hopefully standing as a solid middle ground between flexibility and direction.

Here is a comparison below.

That's the simple change. The more complicated change is below.

Introducing Conflicts

Conflicts represent a character's central dramatic struggle, whether that's against someone specific, the world at large, or themselves. All Conflicts are, at their heart, a question about who the PC is, what matters to them, and what choices they will make.

Each Conflict consists of:

- Its Name, which summarizes what it's about.

- Its Description, which adds more detail to it and presents its primary narrative tension.

- Its Questions. Answer the first two when you gain the Conflict, then discover or explore the rest over time through play.

- An Item that represents your Conflict, often a token or symbol of your struggle rather than something concretely "useful" in the game's mechanics.

- Its Feature, which offers unique mechanics that provide both benefits and drawbacks.

- Its example Terrible Truth. Revealing a Terrible Truth about your Conflict is something you can choose when you mark all conditions and therefore Reach Your Limit.

Features can be pretty crazy, sometimes introducing new stats, mechanics, or letting you bend the rules in unique ways. This keeps the Conflict relevant in play, but can be pretty complex. That's why, by default PCs won't start with a Conflict, and they can only have one Conflict at a time. Once a player has become familiar with the core rules and wants to start pushing their character, they can always gain a Conflict as an advancement. This will hopefully also cause characters to flesh out and open up about their past gradually but meaningfully, rather than spouting it all at once during initial introductions.

Resolving a Conflict is very open-ended. While some guidance is given, it's ultimately up to the PC when their Conflict has resolved. When a Conflict is resolved, the PC loses access to it entirely, but they unlock an Advancement that can't be gained any other way, either gaining a new move unique to their class, or unlocking their Moment of Heroism.

Later on, if the character develops further, they can always gain a new Conflict as another advancement later.

There are currently 22 amazing Conflicts in the Final Alpha, including Bloody Vengeance, Born Yesterday, and Dark Whisperer. Here is a full example of a fourth one below.

Example Conflict - Alter Ego

You have a second identity that empowers you to act in ways you normally can’t. How hard could living two lives be?

Questions: What is your alter ego’s name and appearance? What other PC knows about it? What consequences from your alter ego’s actions might come back to bite you? Who do you want to keep your alter ego hidden from?

Item: A clear mask, outfit, or symbol of your alter ego.

Feature: The Mask - When you first gain this Conflict, write down two of your stats. While you’re acting as your alter ego, these two stats switch numbers. When you Enjoy Downtime, you can spend 1 Treasure to change either or both chosen stats.

When you don or doff your alter ego in a difficult position, or in witness of someone you don’t have a Bond with, mark a condition. How does your alter ego’s appearance or behavior change to reflect this?

Example Terrible Truth: A powerful enemy has traced your alter ego back to you and acted accordingly.

Like everything in the Final Alpha, the example above is greatly subject to change before it even releases.

I hope the idea of Conflicts brings you as much excitement as it does to me.

Thanks for reading,

Spencer

Co-designer Commentary - Helena

I don’t remember where I read it first, but one design truth about TTRPGs that has stuck with me throughout the years is the idea that TTRPGS are unique because they are the only storytelling medium where the protagonists and the audience are one and the same. This means many things but, in this case, I think it’s important to remember that having “good” characters—i.e., interesting, dramatic, and/or enjoyable ones—is as much an effort in character creation/roleplaying in general as in how we react to the rest of the players character creation/roleplaying. In other words: if the rest of the players don’t care about what a player is doing with their character, it doesn’t matter how well they’re doing, their effort will most probably go to waste.

Another aspect of this is that we need to walk a narrow line between offering a way for players to get inspired with their character creation/development and being too inspiring, to the point of players feeling like they have to create characters in a certain way to play DW2. So, as with everything else, your feedback will be invaluable to see how to thread this needle correctly, as it were.